Preservation Policy for a Changing World

How we choose to save the past has everything to do with the present. In the United States, federal preservation laws have often followed public interest in saving a certain history and its corresponding structures. Today our biggest challenge is climate change, and while there has been interest in adapting preservation methods to address this, no major federal law has followed. A look back at the history of preservation law can help trace how the field has developed and perhaps point towards its future.

The classic text Preservation Comes of Age traces the origins of historic preservation in the United States to the rapid change of the early 20th century. Within a few generations, industrialization and population growth transformed the lives of most Americans, prompting some to start protecting relics of older ways of life. Following the interests of the cultural elites, historic preservation entered into federal legislation for the first time in the United States with the 1906 Antiquities Act. This law was a victory for preservationists, as the President could to declare historic landmarks, structures, and objects on areas of federal land and institutions could excavate and study these areas. The Antiquities Act is still relevant today; President Obama designated 29 national monuments with this law and a total of 157 monuments have been designated by 16 presidents.

Montezuma’s Castle in Arizona was one of the earliest National Monuments designated by President Theodore Roosevelt under the Antiquities Act.

While the Antiquities Act remains useful, preservation law still required updates for changing times. Private philanthropists financed many early preservation efforts – like the Rockefellers of Colonial Williamsburg – but federal and state institutions stepped in following the economic crash in 1929 to care for a growing number of historic properties. As part of the New Deal, the Civilian Conservation Corps surveyed sites, buildings, and federal records in an attempt to display American history. In 1935, federal protections for historic properties were again supported by Congress through the Historic Sites Act.

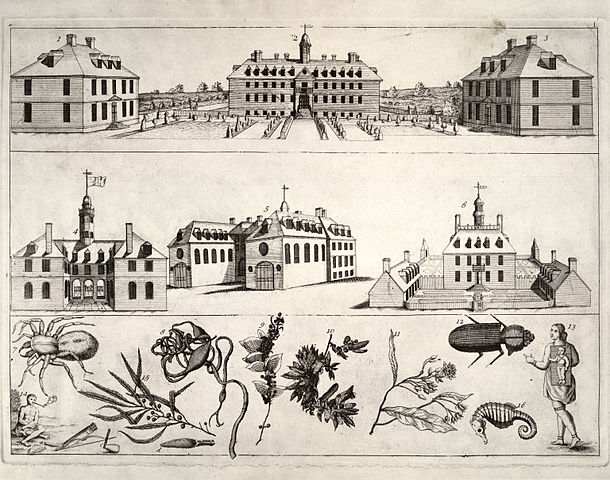

The Bodleian Plate was engraved in the mid-18th century and depicted parts of Williamsburg, Virginia. The plate was used as a reference during the restoration and reconstruction of Colonial Williamsburg. Today Colonial Williamsburg serves to both represent the history of the 17th and 18th century colonial capital, as well as the early history and development of the historic preservation movement in the United States.

Negative public reactions to comprehensive urban renewal policies of the 1960s spurred the next phase of preservation reform. This period saw the founding of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the National Survey of Historic Buildings and Sites, and the National Register of Historic Places. In 1966, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), which was designed to recognize and protect irreplaceable buildings. The NHPA places value on a building’s historical significance and the presence and condition of original materials – 50 years later, these criteria are hotly contested as preservationists are rethinking the balance of structural integrity and value.

These images celebrate the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, which took place in 2016. Among the most notable portions of NHPA, Section 106 requires federal agencies to determine whether their actions will cause irreparable harm or damage to historical sites before they go ahead with planning.

Sustainable development – a term that has included the adaptive reuse of historic structures – has informed the preservation movement since the 1970s. Environmental activism pushed forward federal legislation to protect the environment and in doing so tangentially impacted preservation practices. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 requires builders to prove that new structures will not negatively impact the environment and so also encourages building reuse. With this law, adaptive reuse became more economical and practical.

Preservation practices today are guided by these laws and many others, but no regulation yet exists in response to climate change. This should not be mistaken for a lack of public interest, though. State governments, local governments, and community activists across the country have already begun to develop and implement preservation responses to a changing climate. Examples include the Weather It Together Project in Annapolis, Maryland and the New York State Historic Preservation Plan, which encourages organizations to learn from Hurricane Sandy. The Puyallup Tribe in the Pacific Northwest produced this climate change impact assessment with adaptation options. On the federal level, the National Park Service has begun writing climate change into their planning documents, using some of these resources. Notably, the federal government has not issued a comprehensive climate change strategy that includes cultural resources.

While the actions of these organizations may not translate into national legislation, the field is moving forward and responding to the most pressing issues of our current moment. Will we see a new federal preservation law in response to climate change in the coming years? Perhaps, but until that time innovative local and international conversations will continue to spur interest and action.